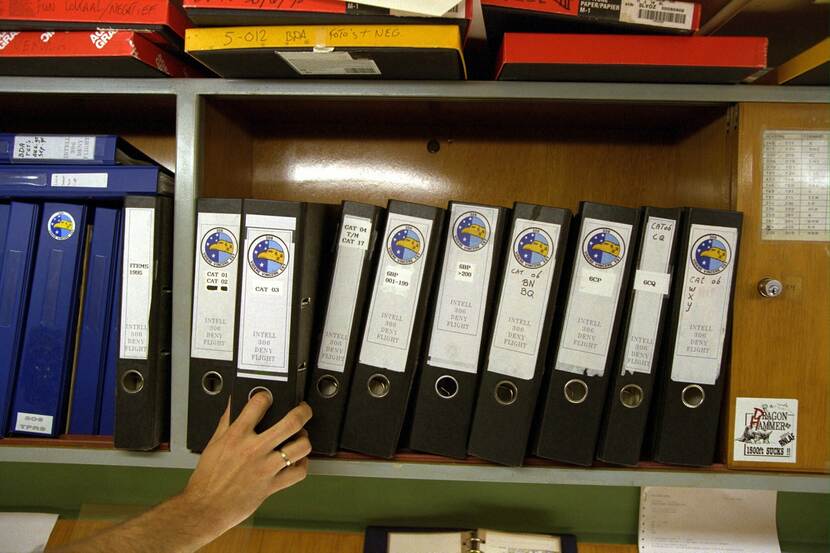

A new book by Bob de Graaff, Professor of Intelligence and Security Studies at Utrecht University, is due to be published this December. Ongekend en onderscheidend describes the hundred-year history of the Netherlands Defence Intelligence and Security Service (DISS). In our interview with Professor De Graaff he talks about his research for the book.

What was the most surprising aspect you encountered in the course of your research? ‘What surprised me most is how long it took before the Netherlands had a military intelligence service operating at its current level. My historical account starts in the year 1912 with the Foreign Armies agency. It wasn’t until some 20 years ago that the service really started professionalising.’

‘You see people becoming successful in applying a particular method, which they are then forced to abandon in the face of a new threat.

What changes have occurred in the service?

The activities of the service are governed by the threat landscape. If that landscape changes, procedures must change accordingly. Before the Second World War the Netherlands had lived with the notion of being a neutral country for years. The intelligence service supported that view. This period is followed by one of alliances. We were forced to think beyond our borders and involve other countries in our decision-making. At the end of the Cold War, crisis containment operations became the dominant perspective, which required a different approach yet again. Then we were confronted with 9/11, which upended all our existing procedures. Up until then anti-terrorism operations had mostly been judicial in nature, but all of a sudden now also required a military approach. We are currently shifting our operations to the cyber domain, albeit relatively late.

‘Late’ in what way?

‘You see people becoming successful in applying a particular method, which they are then forced to abandon in the face of a new threat. The same was true for the cyber domain. Shortly before, the service had achieved successes with SIGINT, gathering intelligence from the airwaves or cable. It was difficult to let go of that approach. People may do things they are really good at, but are they actually doing the right things?

The service’s core business is in fact early warning and foresight. But throughout its history you can pinpoint certain paradigm shifts the service had not foreseen. It takes five to six years on average to adjust procedures to a new paradigm. For example, after the Cold War the service held on for a long time to its old working methods of establishing the order of battle and identifying materiel. Little attention was paid to intentions or to the fact that the distinctions between strategic, operational and tactical were much less well-defined in crisis containment operations than during the Cold War.

But the service did foresee the interstate conflict that we have today. The service continued to keep a close eye on the Russian Federation after the Cold War and identified several major changes which fostered the more aggressive Russian foreign policy.’

‘What the service has been doing for years is write reports about the truth, dump them on the client’s doorstep and walk away shouting: ‘You are stupid if you don’t use it.’

Is the service currently better positioned to anticipate and respond faster?

If you see a change coming you need to take several steps. First of all, what new procedure do we need in light of this paradigm shift? Secondly, are the legal framework and regulations appropriate for the new situation and can I anticipate that? You would not believe the time it takes to pass a law to support a particular procedure. And thirdly, how do I inform my clients? Because they often don’t want to be bothered with crises of the future. They are preoccupied with the challenges of today.

How do you think NLD DISS can convince politics and society to pay additional attention to crises of the future?

‘What the service has been doing for years is write reports about the truth, dump them on the client’s doorstep and walk away shouting: ‘You are stupid if you don’t use it.’ But what you need now more than ever is a service that communicates well, also to the outside world. We have seen the US and British services sharing their findings on the Russia-Ukraine conflict. That requires strategic communication involving having discussions in a democratic context without being accused of manipulative behaviour. Herein lies a great challenge for the service.